No Time to Leave pt.2

This is not an anti-all-inclusive essay. I have already bought into the model, and in Mexico, the surrounding ecosystem still works. The resort captures spending, but the destination still circulates it. What I found in Jamaica is a system so frictionless inside the resort gates and so hostile outside them that even a visitor who arrived determined to spend in the local economy eventually stops trying.

Links to all parts (Part1) (Part3)

Part 2: Jamaica Doesn't Want Your Money

The Pricing Inversion

Ricky showed us what Jamaica could be. The rest of the week showed us what it costs.

A few days later, we walked to the Ocho Rios Jerk Centre — back through the resort's service corridor to the gate, then out to DaCosta Drive and across the road on foot because there is no crosswalk. Half a mile total. Not far. But every step of the way is designed to make you feel like you're going the wrong way, and in rain or real heat, most guests would never attempt it. We ordered a jerk mixed platter, a rum punch, and a rum cream on ice. The bill came to $43 USD. We paid in cash with a $50 bill and left the change as the tip.

The exchange rate the restaurant applied was 120 Jamaican dollars to 1 USD. The Bank of Jamaica's posted rate that week was approximately 156 JMD to 1 USD. The restaurant wasn't close with its exchange rate. It wasn't rounding. It was applying a rate quoted to us in a cash transaction, amounting to a hidden 23% surcharge on every dollar spent. Invisible unless you already knew the official rate, which most tourists don't.

Unfavorable exchange rates at street-level businesses are not unique to Jamaica. They occur in Thailand, Bali, Mexico, and anywhere tourists pay in foreign cash. But in those destinations, the surcharge is one friction among many rewards. In Jamaica, it stacks on top of the taxi markup, the shopping parity, and the lack of any countervailing reason to keep spending outside the gate. Each friction is survivable alone. Together, they make a strong argument for the wristband.

I mentioned the rate to Jamaicans at the resort during separate, unprompted conversations. None of them was surprised. A Jamaican family waiting in line for omelets at the breakfast buffet nodded knowingly.

But it was our bartender who made the math impossible to ignore.

He was Jamaican, born and raised. He asked what we'd paid at the jerk center. When I told him, he called it "rubbish." He said his street-side jerk guy, a few miles outside of town, would have charged less than $10 for the same food. Not a comparable meal. The same food. Then he made me the identical rum punch I'd paid $16 for at the jerk center, three rums, same recipe, and slid it across the bar. Less pretty glass. More blended than layered. Equally drinkable. And unlimited.

The next afternoon, I sat down at the resort's beachside Jerk Hut, Rasta-colored picnic tables in the sand, mountains behind, the bay in front, and the cook loaded my plate without a word. Chicken, peas, and rice, festivals, "volcano" sauce. I washed it down with Red Stripes. As many as I wanted. Included. The same food I'd walked half a mile on broken sidewalks to pay $43 for, served ten steps from the ocean, for nothing. The cook just shook his head when I told him what we'd paid in town. He didn't need to say anything.

The wristband won the argument right there on the beach. Belly full, sun included, and Ricky still in the mountains without a phone.

The Shopping Test

The pricing problem doesn't stop at restaurants.

I wanted to bring Jamaica home. I wanted to buy the rum, the coffee, the sauce, and the products this country is famous for, at the source, with money that stays on the island. So I price-checked Jamaica's flagship products at the source, not at tourist shops, but at the stores where Jamaicans buy groceries. General Food is on Main Street in the Ocean Village Shopping Centre. Fontana, Jamaica's largest pharmacy chain, which Jamaicans themselves consider the premium option. The Chinese supermarket where Ricky had taken us earlier in the week. These are the stores a tourist finds because they're visible and central. Locals told me cheaper options exist further out in the residential areas, but a visitor without a car and local knowledge will never reach them. The prices I'm about to cite are already the best-case scenario for a tourist making an effort.

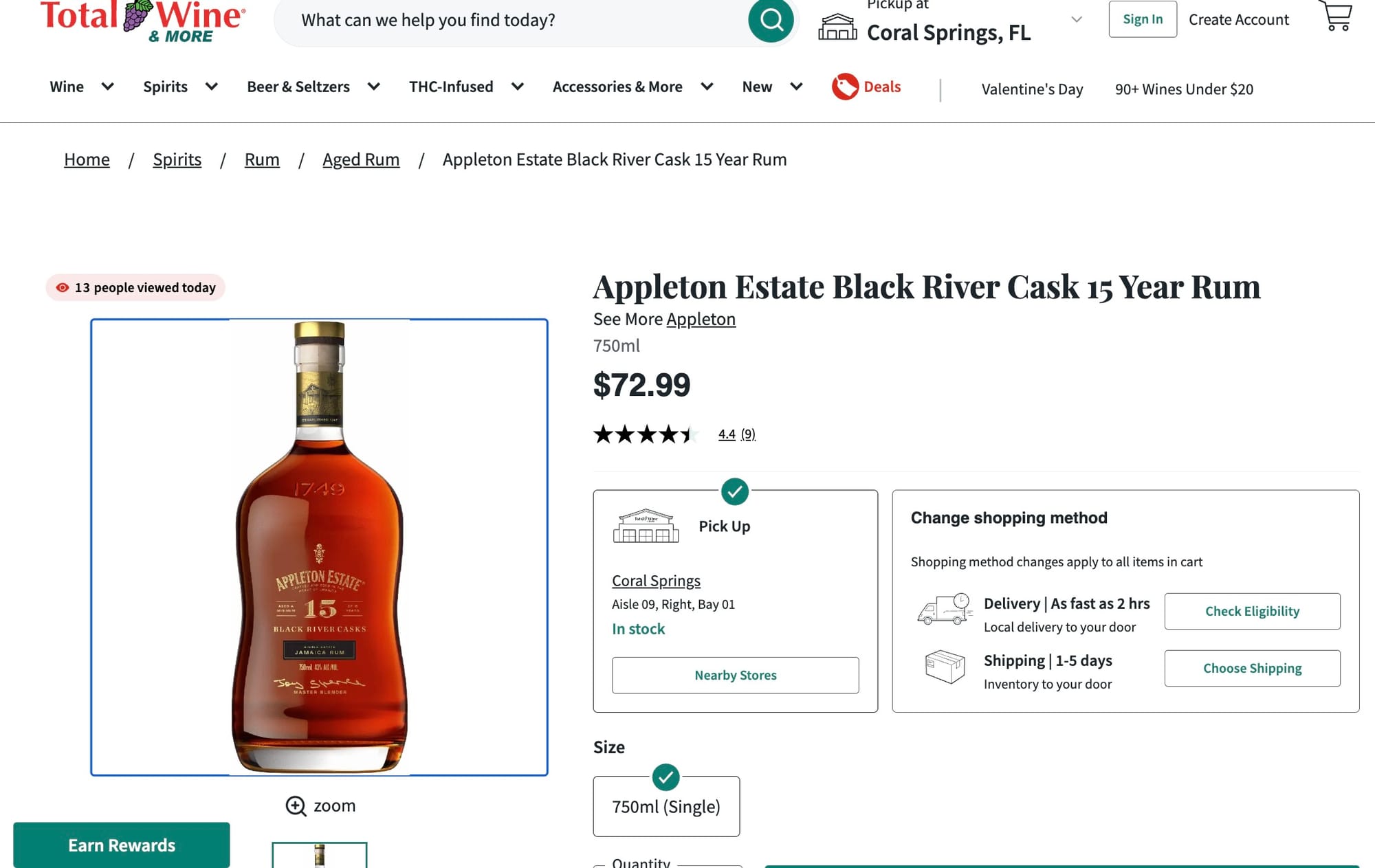

Appleton Estate 15 Year, Jamaica's flagship aged rum, distilled and aged on the island, was $74 USD. The same 750ml bottle retails for roughly the same price at a Total Wine in Florida. No origin advantage. No reason to carry a glass bottle home in a suitcase when I could buy it for the same price a mile from my house. I bought the $15 rum cream and left. The Appleton 21 was $200, dusty stock, visibly old. Twenty-five years ago, on the same island, I bought that bottle for $55.

Blue Mountain coffee, one of the most prestigious coffees in the world, grown in the mountains visible from where I was standing, was priced between $50 and $65 a pound. The same range you'd pay ordering it from a specialty roaster in Brooklyn. Eighty percent of Blue Mountain production goes to Japan. What remains for local sale is priced for scarcity, not for the visitor who flew in hoping to bring home something authentic at a fair price.

Premium is acceptable. Parity is not. In Mexico, a bottle of premium tequila costs a fraction of its U.S. retail price because the country treats origin pricing as a competitive advantage. A visitor pays less at the source because the product is made there. That is the baseline expectation Jamaica's pricing violates.

Some will argue that Jamaica's domestic tax burden (GCT, Special Consumption Tax, distributor margins) pushes local retail prices to parity, through no one's fault. That argument collapsed in April 2025.

When the Trump administration imposed a 10% tariff on Caribbean rum imports into the United States, Appleton's landed cost in Florida rose, yet the U.S. retail price remained the same as what I paid at the source. A bottle of Appleton 15 now crosses an ocean, clears U.S. customs, absorbs a new tariff, pays federal and state excise taxes, and takes distributor and retail margins — and costs the same as buying it in Jamaica. Whatever the cause of parity pricing, whether tax structure, brand strategy, or indifference, the visitor experience is identical: no origin advantage, no reason to buy, and another incentive to stay inside the resort where the drinks are included.

Every one of these moments is a small decision point. And at every one, the rational response is the same:

Go back to the resort. The buffet is included. Why bother?

That's not a tourist being lazy. That's a tourist responding to incentives.

The Unplayed Card

Jamaica has another competitive advantage it is actively squandering: cannabis.

The island decriminalized possession of up to two ounces in 2015. Tourists can obtain a medical permit on-site for as little as $15. The Cannabis Licensing Authority has issued 166 licenses, but the actual number of retail herb houses operating island-wide is roughly two dozen. Jamaica, the country synonymous with ganja worldwide and the home of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh's "Legalize It," should be dominating cannabis tourism the way Napa dominates wine country. Jamaica generated $4.3 billion in tourism revenue in 2024. Its entire legal cannabis industry captured $44 million — roughly a penny on every tourism dollar. In the country that put ganja on the global map, legal cannabis is a rounding error on the tourism balance sheet.

Instead, the informal economy fills the gap. You smell ganja everywhere. It looms over the resort like an unwelcome guest — drifting from stairwells, pool cabanas, balconies, and the far smoking areas near the beach. In town, it seeps from doorways and parked cars. How much is bought by resort guests from street vendors, how much is brought by visitors from home, and how much is by locals is impossible to quantify. But the observation that matters is simpler: between the airport and the resort gate, there is no legal retail touchpoint. No dispensary in the terminal. No branded shop in the lobby. No concierge recommendation. Cannabis is not mentioned at check-in. It does not appear in the promotional loop on the in-room TVs. It is not in any literature left in the rooms. A guest who wants to buy legally has to sheepishly ask a staff member where the herb shops are, or be motivated enough to walk into town on their own. The demand is clear. Jamaica is not capturing it through any channel the government can see, or the economy can count on.

We walked to Rastafari House, the closest licensed dispensary to Moon Palace. One young woman stood behind a glass partition, with marijuana flower and a single edible product — a $40 four-pack of 30mg gummies that would flatten a casual consumer — and no guidance was offered. The infrastructure for something better exists. Jacana, a licensed Jamaican cannabis company with a 100-acre farm in St. Ann, operates a dispensary in Island Village, offering flower, vapes, gummies, and CBD products in a retail environment reviewers have compared to dispensaries in Colorado. Delivery services operate in Ocho Rios and will bring products to hotel lobbies. Some accept credit cards, and some let you pre-order before you arrive. But none of it is connected to the resort ecosystem. The high-value consumer is sitting by the pool with a wristband on, and nobody has any incentive to reach them.

The Property That Tells the Story

Palace Resorts is the only operator building at scale in Mexico, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic simultaneously — the clearest lens into how the same company behaves differently across countries.

Moon Palace Jamaica is not a purpose-built Palace property. My wife and I stayed at this same footprint twenty-five years ago, when it operated as the Renaissance Jamaica Grande. Before that, it was two separate hotels built in the late 1970s — at least eight identities across five decades on the same 17-acre site. No purpose-built resort changes hands this many times. This is a lease nobody wants to renew. Palace acquired it in 2014 and reopened it in 2015.

Palace's own press materials cite a total investment of $250 million in the Ocho Rios property, covering the acquisition, a $50 million renovation, and the addition of a low-rise Cabana building reserved for vacation club members. But when I was there, the hot tubs had broken jets with inconsistent water temperatures. Concrete in the pool area showed visible wear. The property does not look like a quarter of a billion dollars. It looks like a resort being maintained at the minimum viable level while the real money goes elsewhere.

Elsewhere is not hard to find. Beach Palace in Cancún, Mexico — Palace's oldest family property, also built in the 1970s — closed in August 2025 for a $60 million gut renovation of 287 rooms, bringing two aging properties from the same era to a close. One gets reinvested in. The other gets maintained. Repeat guests and travel advisors consistently describe the Jamaica property as a franchise afterthought.

The real investment is going to Montego Bay. Moon Palace The Grand, a $700 million, 33-story development with 1,200 rooms and overwater bungalows, the tallest hotel in the Caribbean when completed, with Prime Minister Holness himself at the August 2025 groundbreaking. Palace CEO Gibran Chapur also announced a $5 million community package: 28 acres for staff housing, upgrades to a local primary school, and the redevelopment of Success Beach in Rose Hall into a public beach. That is 0.7% of the project's cost. For every dollar Palace spends building the resort, less than a penny goes to the community around it.

In the Dominican Republic, Palace is building something far more ambitious. Moon Palace The Grand Punta Cana is a $1.5 billion project designed to hold 5,000 visitors a day — and alongside it, Ciudad Palace: 1,800 apartments with schools, parks, retail, and essential services for the 5,700 workers who will make it run. The containment is total. But so is the investment in the people who operate it. In Montego Bay, the workers get 28 acres and a school upgrade.

Montego Bay is the upgrade Ocho Rios will never get. Punta Cana gets a city. MoBay gets the Caribbean's tallest hotel. Ocho Rios gets broken hot tubs and a property that hasn't been meaningfully renovated since 2015. Palace has announced no future investment plan for Ocho Rios — no renovation, no expansion, not even a press release. Every corporate communication references the 2015 opening as a completed chapter and pivots to MoBay as the future. That is not ambiguity. That is a company managing an exit on its own timeline.

The town has been declining long enough to confirm that reading. When we were here in 2000, Ocho Rios was a functioning resort town. Cruise ships were docking, shops were full, and restaurants were busy. In 2006, the town received 865,000 cruise passengers. By 2011, after the Falmouth cruise port opened to the west and began absorbing the megaliners, that number had dropped to roughly 400,000. The president of the St. Ann Chamber of Commerce warned publicly that the town could "die a slow, painful death." Beaches Ocho Rios, the Sandals family brand, closed in May.

Ocho Rios is not a town in transition. It has been losing ground for fifteen years. The easy response is to call it an outlier — a declining corridor that was already struggling before the hurricane, before Palace pivoted to MoBay, and before Beaches closed. But Ocho Rios is not the outlier. It is the canary. It has the closest major resort to a functioning town center on the north coast, the shortest walk from the gate to local businesses, and the most natural conditions for participation. It is also one of the corridors least affected by the hurricane. The western parishes took the worst of it. Most of the Hyatt and Sandals closures are in Montego Bay and Hanover. I did not see the worst of the island. I saw the corridor that recovered fastest, and I still found every structural problem described above. The difference between storm damage and systemic neglect is visible from the road. Blown roofs, knocked-down trees, damaged tiles, downed telephone wire — that is Melissa. You can see it on the houses between the highway and the resort gate.

Crumbling concrete, peeling paint, broken roads, unmanicured grounds, and sidewalks that disintegrate into gravel take years. The hurricane did not break the taxi pricing, the exchange rate surcharges, the shopping parity, or the absence of local transport infrastructure. Those were all here before the storm, and they will all be here after the last roof is repaired.

Moon Palace is the largest resort in central Ocho Rios. With Beaches already closed, the town has lost one of its anchors. Repeat Palace members and travel advisors expect that once the MoBay flagship opens, Palace will sell the Ocho Rios waterfront land. If that happens, the town loses both.