No Time to Leave pt.3

This is not about crime, or safety, or "the locals." Everyone I met — every bartender, every vendor, every guide, every family — was warm, professional, and often openly frustrated by the same dynamics I was documenting. The people of Jamaica are not the problem. The people of Jamaica are the ones I am writing this for. I did not write this to punish Jamaica. I wrote it because silence, after what I saw, would be complicity in the thing that is hurting them.

Links to all parts (Part1) (Part2)

Part 3: Wristband Babylon

The Contradiction

Every major resort investment in Jamaica leans heavily on the all-inclusive model. And, by design, all-inclusive is a containment system. When Tourism Minister Bartlett says "tourism must be for all Jamaicans" and Prime Minister Holness calls for community-based tourism that empowers small businesses, they are describing a participation economy — one that requires visitors to leave the resort. Then the government celebrates another 350-room all-inclusive resort breaking ground. Then the system makes leaving irrational. Those two visions are in direct conflict. No one is reconciling them.

We were there in February. Bob Marley Month. His music was inescapable — in the lobby, on the pool deck, drifting from speakers in the hallways. His face was on banners in the streets. I could hear Jamaica everywhere. I just couldn't reach it.

Minister Bartlett himself has acknowledged the cost. In a 2024 post-Cabinet briefing, he stated that only 40 cents of every tourism dollar stays in Jamaica, and that the government needs to "plug the leakages by strengthening the linkages." His number is broad — it includes hotel payroll, local purchasing, and taxes. Jamaica's own minister calls leakage "the major obstacle to sustainable tourism growth."

The picture is worse at the street level. UNEP has found that in most all-inclusive packages, approximately 80% of traveler spending goes to airlines, hotels, and international companies rather than local businesses, a figure the UNWTO has cited as representative of Caribbean tourism leakage. Bartlett's 40 cents and UNEP's 20 cents are not contradictory — Bartlett counts everything that stays in-country, including wages paid by foreign-owned hotels; UNEP counts what reaches the local economy outside the resort walls. Both numbers are damning. The gap between them shows how much of what "stays" never circulates. A January 2025 World Bank report confirmed that the Caribbean's focus on volume and cruise segments has delivered "low tourism spending per arrival, limited fiscal revenues, and placed pressure on island infrastructure."

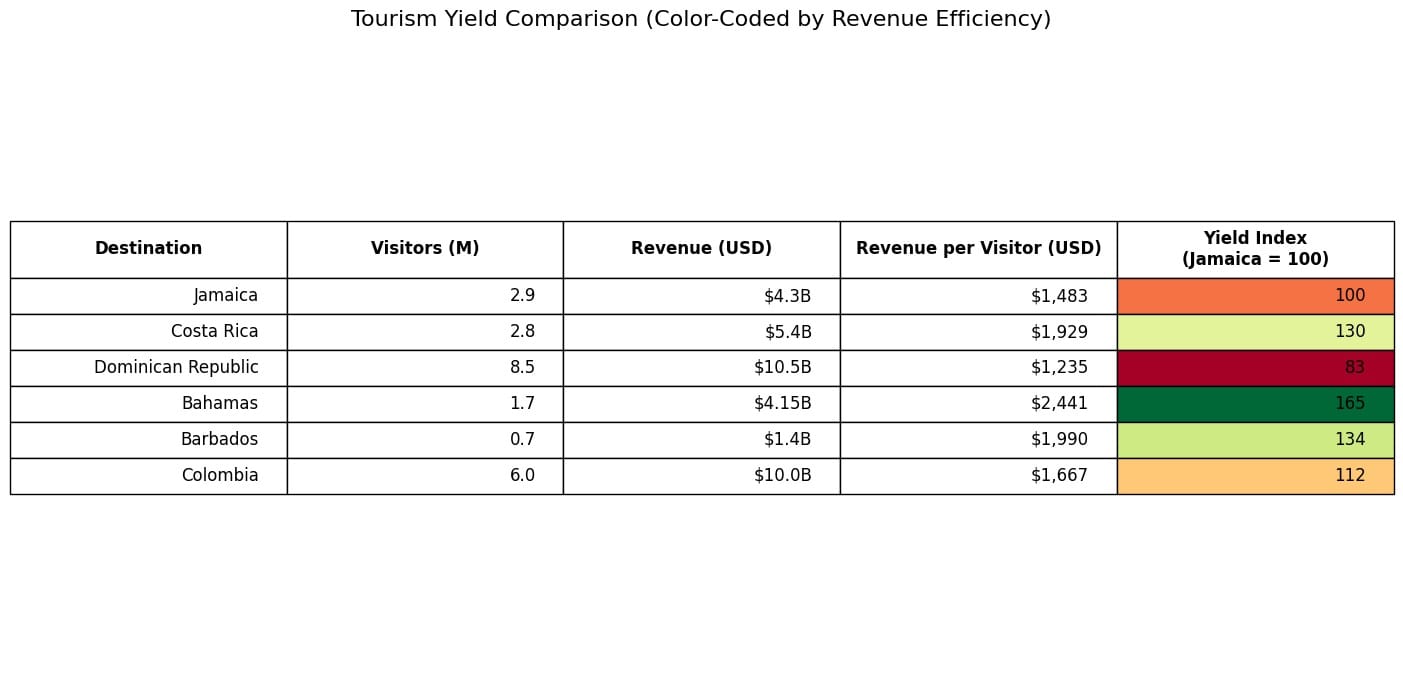

In 2024, Jamaica welcomed 2.9 million stopover visitors, generating $4.3B in tourism revenue. Arrival numbers measure volume. They do not measure distribution.

Tourism revenue and visitor figures are drawn from official government sources for the 2024 calendar year: Jamaica’s Ministry of Tourism (Bartlett, JIS), the Costa Rican Tourism Institute and Central Bank of Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Tourism and Central Bank, the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism, the Barbados Hotel and Tourism Association, and Colombia’s Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism via Migración Colombia. All visitor counts reflect stopover or air arrivals only — cruise passengers are excluded — to ensure comparability across destinations with vastly different cruise volumes.

Revenue figures represent direct tourism receipts as reported by each country’s tourism authority or central bank, with two caveats: Barbados has not published a 2024 receipts figure, so the estimate (~$1.4 billion) is extrapolated from the country’s 2019 pre-pandemic baseline of $1.25 billion adjusted for record 2024 arrivals; and the Bahamas has not released a 2024 total receipts figure, so the number used here ($4.15 billion) reflects the most recent UNWTO direct receipts data from 2019 — the last year for which a comparable figure is publicly available. Stopover arrivals in 2024 matched 2019 levels, so the per-visitor calculation remains representative, and the core comparison holds: the Bahamas generates nearly as much revenue as Jamaica with 40 percent fewer visitors. Per-visitor calculations divide total revenue by stopover arrivals and should be read as approximations — they reflect national averages, not what any individual tourist spends.

Costa Rica is the benchmark that should keep Jamaica's leadership awake at night—nearly identical stopover volumes — 2.8 million versus 2.9 million — and a billion-dollar gap. Costa Rica has no all-inclusive corridor. Its entire model is participation: eco-lodges, rental cars, local restaurants, adventure tours, and national parks with entrance fees that fund conservation. Visitors spend $2,062 per trip, with that money distributed across communities. The Bahamas generates $1.1 billion more than Jamaica, with 40% fewer visitors. Barbados and Colombia both extract more per visitor as participation economies. The table tells the same story six different ways.

The Dominican Republic is the most instructive comparison because it runs the Caribbean's largest all-inclusive corridor — Punta Cana is the Montego Bay of Hispaniola — and still generates $10.5 billion in revenue. The per-visitor number looks modest in the table because the DR has the volume to absorb it: 8.5 million air arrivals and 92,000 hotel rooms across multiple models. But the revenue engine is not just the wristband. Santo Domingo draws business and cultural travelers. Samaná draws eco-tourists. Medical tourism adds half a million visitors a year. The same company, building a $700 million tower in Montego Bay with 28 acres of staff housing, is now building a $1.5 billion project in Punta Cana, with a purpose-built city for 12,000 workers beside it. The DR figured out that containment scales only if you build around it. Jamaica is building more containment with nothing around it.

Jamaica's gap is not volume. Jamaica has the volume. The gap is what happens to each dollar after it arrives.

I know what distribution looks like because my wife complains about it every time we come home from Mexico. Premium tequila and mezcal, liqueurs, plus reposados we can't get stateside. T-shirts. Vanilla. Hot sauce. Ceramics. Jewelry. Gifts for family. By the last night, she's sitting on the suitcase while I rearrange the bottles in bubble wrap and argue with her about checked-bag fees. We spend hundreds of dollars outside the resort on every Mexico trip, and most of it goes directly into the hands of the people who made it or sold it. In Jamaica, I bought two bottles of rum cream, ate at two restaurants, had a Juici Patty, and spent a few dollars at street vendors. Our suitcases came home half empty. That is the distribution gap in a carry-on.

Jamaicans know this. One evening at the resort, we shared a hot tub with a Jamaican couple. These were residents, not tourists, who were using the resort on a local rate. Unprompted, they told us the system was devastating for local businesses. Small restaurants, shops, and tour operators are all struggling because the resorts captured everything, and the visitors never leave them. They said it with a resignation that felt practiced, as though they had made this observation many times to many people and nothing had changed. They felt helpless. Not angry. Helpless. That is worse.

The Comparison Problem

The numbers above show the revenue gap. The experience below shows why.

In Mexico, Jamaica's most direct competitor for North American resort tourism, the government is actively building infrastructure to improve visitor mobility. Mexico's resort corridor has real problems — cartel influence, labor exploitation, environmental destruction from overdevelopment — and no honest comparison pretends otherwise. But the visitor-facing infrastructure works. When Cancún's taxi system became a known point of exploitation, the Quintana Roo state government partnered with ADO to create a $7 bus route from the airport to the hotel zone. In Playa del Carmen, it's $10–15 by bus. Town centers function as independent economies. A visitor at Moon Palace Cancún can walk out the front door, catch an affordable bus, eat tacos at a street stand for $3, browse a public market, and be back at the pool in two hours, having spent $30 in the local economy. Excursions compete on quality and price: cenotes, archaeological sites, cooking classes, and marine parks. The system is designed so that leaving the resort is easy, affordable, and rewarding.

In Jamaica, leaving the resort feels like swimming upstream.

Excursions from Ocho Rios are largely interchangeable, not because operators lack talent, but because the distribution channel flattens them. Dunn's River Falls is the only standout attraction in the corridor. Beyond that, the resort lobby offers the same snorkeling loop, ATV route, and generic island tour. The concierge desk is the bottleneck, and operators who don't pay the commission don't reach the guest. Jamaica has Blue Mountain coffee estates, Port Royal's pirate history, the Blue Lagoon, and one of the most distinctive food cultures in the Caribbean. But a visitor looking for a jerk pit where locals eat or a rum bar with history has no structured way to find it. No app. No walking map. No shuttle. Just the same catamaran as everyone else.

Ocho Rios is also constrained by cruise logistics — and this matters more than it might seem, because cruise passengers are the only reliable foot traffic the town has left. The resorts do not send guests into town. The all-inclusive model is designed to prevent exactly that. So local businesses — the jerk stands, the craft vendors, the taxi operators — depend almost entirely on the cruise ships. In February 2024, a docked cruise ship slammed into the port's main pier. The pier was closed for nearly twenty months, with Hurricane Melissa further complicating repairs. In just the first three months, 21 cruise calls were diverted, rerouting more than 81,000 passengers and resulting in an estimated $6 million in lost local revenue. Craft market vendors were reduced to rotating shifts at a temporary facility.

What They Have Tried

People in Jamaica see the problem. Some of them have been working on it for years.

The institutional response is substantial: a Tourism Enhancement Fund financed by a $20-per-visitor departure levy, a Tourism Linkages Network with five sub-networks connecting tourism spend to the domestic economy, an Agri-Linkages Exchange that has traded over $1 billion in produce between local farmers and hotels, nearly 30,000 certified tourism workers, a Gastronomy Academy, and a "Local First" policy announced weeks before Hurricane Melissa requiring that Jamaican farmers and artisans get first opportunity to supply hotels. In Treasure Beach and Portland, community-based tourism cooperatives have built a working alternative from the ground up: small guesthouses, local guides, and farm-to-table dining.

But none of them have reached the corridor where most tourists actually stay. The Agri-Linkages Exchange connects farmers to hotel kitchens, not to visitors. The Gastronomy Academy trains sous-chefs for resort restaurants, not street vendors for tourist foot traffic. The "Local First" policy was announced two weeks before a Category 5 hurricane. Treasure Beach works because it was built from the community up, in a place where all-inclusives never took hold.

And the Tourism Linkages Network, for all its structural ambition, has not produced a single visible artifact that a tourist walking out of Moon Palace would encounter: no branded shuttle, no walking map, no certified local guide like the one Ricky could be, no digital payment bridge between a visitor's phone and a vendor's hand.

The institutional intent is real. The visitor-facing delivery is invisible. And in tourism, what the visitor cannot see does not exist.

The Recovery Contradiction

Hurricane Melissa's destruction was real. The government's response was genuinely impressive: a recovery task force was activated within a day, major resort areas reopened within six weeks, over 370,000 visitors were welcomed by late December, and $331 million was earned in the initial recovery window.

Leadership framed the moment as an opportunity to "rebuild, reimagine, and reposition." But reimagine what, exactly?

The answer is visible from the investment pipeline. The government has designated a "Tourism Innovation Township" in Rose Hall, Montego Bay — over 5,000 rooms across Moon Palace, Hard Rock, Unico, and Iberostar, all within walking distance, which Bartlett calls the densest concentration of hotel rooms in the Caribbean. By 2030, Jamaica projects 10,000 new rooms islandwide. Nearly all of them are in one parish. Portland has a six-room celebrity hideaway. Treasure Beach runs on guesthouses. Kingston's cultural tourism barely registers in the ministry's investment pipeline. The rooms are not spreading across Jamaica. They are concentrating in the corridor that took the worst hurricane damage — where Sangster's passenger traffic dropped 73% in November 2025, where three Sandals properties won't reopen until May 2026, and where Palace broke ground on a $700 million tower exactly two months before a Category 5 storm erased the demand projections the investment was built on.

The recovery itself reveals the hierarchy. Ocho Rios had guests back the day after the storm. Negril reopened in six weeks. Portland and Kingston were barely touched. But in MoBay, where all the money is going, World Central Kitchen was still serving meals from the Convention Center in December. The corridor with the most immediate revenue-generating capacity — Ocho Rios, already open, already earning, with the closest resort-to-town walkability on the north coast — is getting no investment. The corridor that is most damaged, years from full capacity, and whose building-on-demand projections were invalidated by a Category 5 hurricane, is absorbing all of it. The resort corridors get rebuilt first because they generate revenue. The communities between them — St. Elizabeth, where the eye made landfall; Westmoreland; Hanover — wait. The same system that routes tourist dollars away from communities also routes reconstruction dollars away from them.

And none of it works without an airlift that doesn't exist yet. Sangster handled 4.47 million passengers in 2025, down 11.6% from 2024. Jamaica is building thousands of rooms while its passenger count is falling. The JTB projects a 43.8% increase in seat capacity by 2026, but that growth is coming off a post-hurricane low, not from a structural expansion of its route network. The supply chain tells the same story: Jamaica imported $1.3 billion in food in 2024, 60% of it going to hotels and restaurants, while only 15% of what hotels serve comes from local farmers. A decade of agri-linkage programs has not moved that number. Every new room is another mouth the island cannot feed locally, another supply line running from Miami to a buffet that a guest never leaves.

Ricky cannot replace his phone. Craft vendors at the Ocho Rios pier are rotating shifts at a temporary facility. Jerk stands, and taxi drivers compete for traffic that the resorts are designed to prevent. Every month without parallel investment in local transport, local pricing, and local distribution is a month the traditional economy loses ground; it will not recover.

This is the inflection point. There is a window after a disaster, brief and politically charged, in which structural change is possible. Decisions made in this window shape the next decade.

Jamaica is focusing its recovery efforts almost entirely on increased containment and on a larger scale.

Supply has been rebuilt. Circulation has not.

If recovery means rebuilding Babylon with nicer furniture, then the structural problem does not just survive the storm; it persists. It calcifies. The all-inclusive footprint expands. The local economy contracts. And the gap between the wristband economy and the mountain economy becomes permanent — not because anyone chose that outcome explicitly, but because no one chose to prevent it while the window was open.

The wristband goes back on.

The local economy stays outside the gate.

And the next visitor with options — not just a Palace member with Cancún in the system, but any repeat Caribbean traveler who has been to Mexico, Aruba, or the Bahamas and felt the difference — makes the same quiet calculation I did:

Next time, Cancún.

That is the calculation Jamaica cannot survive at scale. Not after a Category 5 hurricane. Not with $1.3 billion in food imports. Not with Beaches already closed and Ocho Rios losing ground. Every visitor who makes that calculation and does not come back takes recovery dollars with them — dollars the island was counting on, dollars that could have reached Ricky and people like him. Jamaica is not losing tourists to a competitor. It is losing them to its own friction.

What Alignment Would Actually Look Like

The problems are structural, but they're fixable. None of them requires foreign aid or new legislation. They require alignment between what Jamaica says it wants and what Jamaica actually incentivizes.

The tools already exist. Route taxis run on DaCosta Drive for a dollar — but there's no sign, shuttle, or concierge to point a tourist toward them. Jamaica has Lynk, a mobile wallet integrated with the country's central bank digital currency, but it requires a Jamaican national ID, so tourists can't use it. There is no Venmo, no CashApp, no tap-to-pay at the jerk stand. A visitor carrying no Jamaican cash and no way to pay digitally is captured by the resort's credit system by default. Appleton Estate and Blue Mountain coffee are marketed globally as reasons to visit — but they cost the same at the source as they do in Florida. When a tourist can Google the stateside price and see parity, every "buy local" message collapses.

What doesn't exist yet could. Certified micro-excursions that aren't booked through the resort lobby on commission. A jerk seasoning workshop, a rum distillery walk-in tasting, and a fishing trip with a local captain. And resort approvals that come with conditions: a shuttle to the nearest town center, a percentage of excursion bookings routed through local operators, and a "local experience" package alongside the wristband. The resorts will resist this. The local economy needs it.

Jamaica does not need more rooms. It needs more access.

The Missing Bridge

And what does any of this mean for a man in the mountains with no phone and no roof?

Ricky is one person. I know he sounds like someone I invented to make an argument — the unlicensed guide with no phone, the hurricane-damaged house, the quiet dignity. He is real. The photos from that afternoon show him standing next to my wife at the Silver Seas railing, looking out at the reef. Ricky is the name he gave us. I'm not sure if it is the one on his ID. And the question the essay cannot answer is how many Rickys exist in Jamaica. The informal tourism economy — unlicensed guides, street vendors, small-boat captains — is populated by thousands. Most never had a booking system, a resort contract, or a path to the guest in the first place. The hurricane made his situation visible. The system made it permanent.

There is no formal, visible, frictionless pathway for someone like Ricky to participate in the tourism economy at scale. Worse: the informal pathway he has built for himself is one that the system actively polices.

No integrated local guide certification linked to resort booking systems.

No structured micro-excursion platform that connects mountain residents to hotel guests.

No transportation infrastructure that reliably brings visitors into town without a toll.

No designed bridge between the wristband economy and the mountain economy.

No affordable way for a man without a phone to get credentialed, get listed, or get paid.

If we had followed the containment incentives, Ricky would remain invisible. That is what distribution means in practice — not abstract GDP, but whether someone with talent and initiative can reliably access visitor spending without relying on a chance encounter with the one couple who decided to walk.

Ricky should be winning in this system.

He is not.

That is not a failure of culture.

It is a failure of design.

Marley warned about exactly this. Babylon — not as metaphor, not as album art, but as a specific accusation: a system that extracts while protecting incumbents, that processes people while excluding the vulnerable.

And the economic architecture surrounding every all-inclusive in Jamaica looks a lot like the thing his music was written against. Ricky, standing outside the resort gate in his blue cap, unable to replace his phone, is exactly the person Marley was singing about. Jamaica put Marley on the banner and kept building Babylon.

The Reality

I arrived with goodwill, alternatives, and money to spend. At checkout, the front desk cut the wristband off my wrist and pointed us toward the airport shuttle. No last stop in town. No suggested detour. The containment system's final act is to sever the band and route you to departures, where the only remaining spend is duty-free. If a visitor has any dollars left to distribute, they go to the airport gift shop, not the jerk stand. The buffet was fine. The pool was fine. The staff was warm and professional. But I didn't fly to Jamaica for a pool. I flew to Jamaica for Jamaica.

No other Caribbean island has Bob Marley, jerk chicken, Blue Mountain coffee, Appleton rum, dancehall, the Blue Lagoon, Port Royal, and Ian Fleming's writing desk all within driving distance. And nearly all of it sits outside the gate, which is exactly why the gate exists.

The government says tourism should empower small businesses. Then it builds systems that bypass them. The government says recovery is an opportunity to reimagine. Then it celebrates the same all-inclusive model that created the problem.

Liberation is not a soundtrack. It is a policy. And Jamaica does not have one.

In Dr. No, the villain has a lair, a plan, and a name. You find him, and you stop him. Jamaica's tourism economy has no Dr. No. There is no villain in a chair. There is no lair to destroy. There is only a system in which every actor — the resort, the ministry, the exchange bureau, the licensed guide — behaves rationally, and the country still loses.

The world changed. Jamaica's tourism architecture did not.

Nostalgia is not a business model. Capture is not development. And when participation is harder than containment, containment wins. That is not a culture problem. It is a design problem. And the window to fix it — the post-hurricane moment when structural change is still possible — is closing.

And the system is working — just not for the country. Ricky is still in the mountains without a phone. The wristband stays on. There is no time to leave.

I'm happy to publish a response or correction from the Ministry of Tourism, JTB, or any operator who believes I'm missing context, and I'll update any factual point with documentation.*